April 11, 2017

by GForce Software

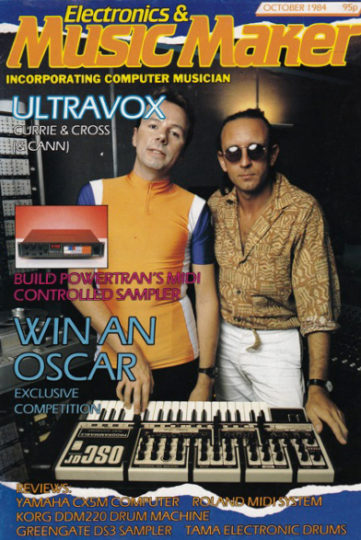

Although probably best known to many for his pioneering synth work with Ultravox, Gary Numan & Visage, Billy Currie has also enjoyed a successful solo career since the release of his first album ‘Transportation’ in 1987.

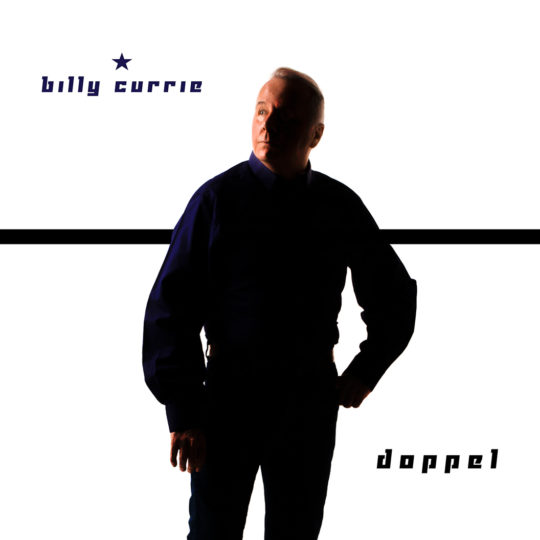

At the time of this interview Billy had just contributed patches for the RE-STRINGS Rack Extension and released his tenth album, ‘Doppel’ which gave us the perfect opportunity to sit and chat tech with one of the icons of synthesis who’s inspired countless musicians throughout his career.

Q. You were originally trained as a classical violinist with piano as a second instrument and you famously turned down a place at the Royal Academy of Music in London at the age of 19. With hindsight, is that a decision you’ve ever come to regret?

Sometimes….but that’s not to do with anything artistic, it’s more to do with when certain aspects of my career weren’t going so well and the temptation is to think that things could have been much more simple within the confines of an orchestra. But the idea of it all being mapped out for you just never really appealed to me because I was destined to be an orchestral player and that had been decided for me by someone else. Also, I’d had an example of some of the incredibly difficult Kreutzer Studies, etudes, where you have to do complicated things in various positions – half position, second position, fourth, fifth, sixth etc. – You do a lot of half position with the viola because of C being the lowest note, and that’s real number crunching, especially when you start getting into the late 19th century music. That was a whole area which, especially at 19, wasn’t really for me.

You don’t go into the rock and pop world expecting a simple thing, you’re just 19 and you don’t care. But now I’m older, I do sometimes think about what a very interesting life in that classical area is.

You don’t go into the rock and pop world expecting a simple thing, you’re just 19 and you don’t care. But now I’m older, I do sometimes think about what a very interesting life in that classical area is… and what a huge area it is too.

Q. Later, during those punk days where musical accomplishment was almost frowned upon, did you ever feel that your formal training got in the way?

We were one of the most stubborn bands in Britain, so, no. The reason I didn’t go to the Royal Academy Of Music was that I went to work with some guys who were older than me who were playing blues and jazz. That was literally a cleansing process of getting the formal training knocked out of me. After a while though that also felt like being told what to do so I got mouthy and ended up getting thrown out.

When we got together as Ultravox we quickly became a stubborn, tight unit. I enjoyed mixing it all up and playing a variety of things in different ways but I was very conscious never to do anything too snooty or too clever which would have been a hangover from the classical days. I was fortunate that John Foxx also wanted to experiment as much as me. He was open to anything, even prog type music. I actually wrote this piece that appeared at the end of Slip Away and which is very proggy. We just used to do what we wanted and wouldn’t stop just because someone else didn’t like it.

Q. How surreal was it playing a violin in front of a bunch of gobbing, pogoing punks?

Very. With the Fender electric violin I could be as nasty sounding as anyone else in the band, like in the solo at the end of Artificial Life. I could open up the volume as the band was going through this uptempo change and i’d let it feedback with a heavyweight, nasty feedback that would stop when I hit the string to start playing. I was obsessed with getting distortion from instruments at that time, probably because of all the aggression.

With the violin, there was always the accusation of being a posh wanker though. I always had a lot of respect for Mick Jones from The Clash but I think due to the inverted snobbery that was going on at the time I’m sure he’d have thought of me as a posh wanker. Mind you, I quite liked that. I’m the clever one at the end with all the shit that I can handle – more keyboards please.

Q. Obviously you’re well known for your use of the original ARP Odyssey. What made you settle on that as your weapon of choice?

I hadn’t got a clue really what I was getting. I liked the shape of it and I didn’t want a Minimoog. What’s strange is that the moment I heard the Odyssey, I didn’t really have an appetite for the actual tone. Good keyboards have got a character and a tone and I didn’t really like the quality of the ARP that much. Straight away I had to subvert it with chorus and flanging so I could like it and make it fit in with the band. Again, I used to really think of it as a guitar so that when it came through those speakers it distorted and made the speakers flap.

My first proper solo was on The Man Who Dies Every Day and there’s a bit where I drop low down which is the first time I realised that if you’ve got a good sound you can get the same thing as a guitar where it sustains through and you can then play these notes that have a certain power without getting too complicated. That’s when I ended up doing solos like on Astradyne where it’s really about the notes. That’s what I learned from working with those jazzy-blues guys when I was 19. Just to let an interval sit there….so long as the sound is good.

Q. Bearing in mind this was before patch memories, did you have any techniques for remembering and recalling sound settings?

Because the instrument was black it was easy to use a chalk to mark positions for things like the LFO speed. But you had to have your shit together to make changes live and be prepared that mistakes were mistakes. For example if you went belting into a solo when you left it on a low volume, don’t freak out. It made you think and react quickly.

Q. Aside from your work with Ultravox, you were an integral part of Visage and Gary Numan. In the Bright Sparks documentary, you say that it was the period working with Tubeway Army that helped you hone your trademark Odyssey sound. That must have been a very prolific and exciting period.

It was but it was also quite rigid. I was playing Gary’s music as a live session man and I’d never been in that position before. It was weird but incredibly stimulating to work with another writer. He does a lot of octaves and quite long tracks where you’ve really got to keep alert or else there will be a change that you’ll miss. I wasn’t particularly stimulated by the chord structures – this is where the clever git attitude comes in – and my heart was still with Ultravox. That whole experience of playing live in big places was a great thing for me as it gave me a chance to develop my sound, mostly with the solo on On Broadway. And because I was a guest musician with a name and Gary was a big fan of Ultravox, I could take liberties as well. I occasionally got ticked off for it, especially with Are Friends Electric by playing extra harmonies, thirds and stuff – but they let me get away with it for nearly the entire tour.

It was a great experience to be able to develop my technique. The previous American tour with Ultravox had been a bit stilted and difficult because John Foxx was leaving. I’ve heard some of the stuff we did on those gigs on YouTube and it sounds like we would have probably gone a little more free-form. Some of the versions of He’s a Liquid, that John did later on his Metamatic album had like 10 minute solos and stuff. It’s quite funny hearing it now. But, yea, the Tubeway Army gigs were definitely a step-up in terms of PA and better quality stage to help develop my sound a bit.

Q. Fade To Grey seems to be one of those iconic 80s tracks that’s regularly covered, used for TV or indeed ‘borrowed’. As I recall, it was actually recorded in 1979 at Martin Rushent’s Genetic Studios. How did that track come about?

I’d started working with Visage before the Tubeway Army tour, which changed to Gary Numan after the success of Are Friends Electric. The production was impressive. We were playing on these massive towers each side of the stage and during soundcheck we were clowning around when I noticed that Chris had started playing these chords on his Polymoog. The Polymoog was something I couldn’t afford at the time and if I remember correctly it was about £5k, so it was a nice instrument to have in front of me to play Cars on. Anyway, Ced got this little rhythm playing on the CR78 and that and Chris’ playing made me think “hang on a minute.”

The same thing happened at another sound check and there was something about the way the drum machine was offset that reminded me of He’s A liquid. Also Ced and I had been listening to Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder on the tour-bus so I just asked him to play a groove. Ced could really play and I loved playing with him but at that point I hadn’t actually added anything myself.

Anyway, we knew we were on to something and in a bit of downtime I suggested that we go and put it to tape at Martin Rushent’s studio in Streatley. We banned Martin from the studio but the engineer was Hazel O’Connor’s brother, Neil, and he just got into it from the off. The whole session just went really well. Also, because Chris was a ‘just get it done’ person, instead of my “can we try this amp and this mic?” suggestions, we opted to just DI the Polymoog into the desk and the strength of the instrument came through straight away. It was a fucking great sound. If it had been another instrument which didn’t sound as good, it could have been the end. We could have just left with nothing.

After the Polymoog, we put the drum machine down and then my job was to arrange it….to give it form. Things like getting the harpsichord sound on the Polymoog and following the chords using thirds where necessary. To be honest, when I was doing it I was thinking “Talk about a fucking nursery rhyme. I should be shot!” But at that time I’d become so tuned in to simple melodies and simple parts, and I think, that, plus a desire to have a hit record, stopped me from making things too complicated and instead going for simple hooks. Then I decided how the drums would build, from the hi-hat to the snare, to when the entire kit would come in, the dropdown harpsichord, adding the melody in thirds at the end etc etc.

We did let Martin in at some point, because when I did the Odyssey upwards portamento bit at the beginning, I remember him saying “Fucking nice one Bill” and I was really chuffed. I’d opened up the AR and not the ADSR because the AR always sounded bigger to me, and went down to the bottom A on the Odyssey. While this was all sustaining I didn’t bother closing down the release for fear that I’d fuck it up. Instead I left it hanging and said to Neil “You can fade it out”

Everyone just seemed to tune into the simplicity of it. Something about the beauty of Fade to Grey is that it’s light, it’s kind of European and not been shaped into something. It’s just what it is. I love the lonely vibe of it.

A year later we were in Mayfair Studios and I brought it in as a late arrival to the Visage album because the album was short of tracks. It had no lyrics, just me shouting “Toot City” like a lunatic over the backing track and, credit where credit is due, Rusty and Midge did a great job on it. Everyone just seemed to tune into the simplicity of it. Something about the beauty of Fade to Grey is that it’s light, it’s kind of European and not been shaped into something. It’s just what it is. I love the lonely vibe of it.

Q. The OSCar is another one of the instruments you’re well known for using. Can you tell us a little of how you came to use that?

OSCar came quite late, when we were doing the ‘Lament’ album. The Odyssey had suddenly become unfashionable so I found myself not really using it. The general consensus was “give that one a rest Bill” when Chris Huggett and Paul Wiffen came in, showed OSCar to us and said “We’ve based the first patch on your ARP sound” so I listened to it, played it and liked it.

I’d become tired of the ARP going out of tune all the time and I wanted something more reliable and some more games to play with. I liked the arpeggiator and I liked its proper distortion and overdrive. I used it for a solo on a track called a Friend I Call Desire, right at the end of the album. Then, when we released that album we decided to do a one-off single, Love’s Great Adventure, on which I used OSCar for the solo.

We also took it out live and using the arpeggiator was brilliant. I used to just go nuts, it was great. Also, getting that distorted sound thrown back at you through the wedges of a big PA system….fucking amazing!

Setting that arpeggiator, then changing up a fifth and then bending it, it becomes like a guitar but with it’s own quality, a roughness that was mind blowing.

The band was falling apart by the time we did ‘U-Vox’ but Conny Plank came to my own studio and I did loads of OSCar solos. It was a blast but we were disagreeing in the band so a lot of things got binned….sometimes in favour of brass!

Q. In terms of features it’s reasonably similar to the Odyssey – the duophonic mode in particular – but finally we had patch memories and stable tuning. Also the inclusion of a filter overdrive function seemed to be directly influenced by what people like you and Jan Hammer were doing with ARPs and fuzzboxes. If you had to choose between an Odyssey and an OSCar, could you?

I’ve thought about this and there’s something about the ARP Odyssey that’s a bit closer to my heart. It was my first proper synth.

Q. When it came to the parting of the ways with Ultravox, was pursuing a solo career daunting or something that you’d wanted to do for a while?

We hadn’t actually parted. It was just a very Ultravox thing where no one was saying or doing anything and I started doing a solo album as soon as I got off the U-Vox tour in 87. I was still fully signed up to Ultravox. It was my life and I was passionate about it. I felt that the band would stay together but I wanted to be busy during any Ultravox downtime so I signed a deal with IRS, Miles Copeland’s record label.

Q. I noticed that during your solo albums you moved through the gamut of classic 80s keyboards including the PPG Wave, Yamaha GS-1 and Roland D-50. What are your fave synths from the 80s?

I loved the GS-1. It was big and high quality but I don’t think I used it a lot on my solo albums. I think it was originally made for the small church market in America so that they could get the sounds they needed without buying a huge church organ. I had a deal with Yamaha who stuck with us over the years and when the GS-1 came out I ended up going to Hamburg and sitting with a Yamaha programmer who created some great string sounds for me. I loved playing that instrument and I could play the vibrato with my feet. I’d stand up and rock back back to keep the sustain going and do the vibrato with my foot.

I used the PPG a lot. I got into the Rack Mounted DX-7, the TX-816. I’d got into MIDI in the early days in my own studio for the first couple of solo albums, Transportation and Stand Up and Walk and linking all these things up to get new sounds. I had a Prophet T8, the Prophet Sampler, the Roland D-50. it was like Keyboard City. The Prophet VS was used a lot. I really liked the joystick and the way you could morph between sounds.

Q. At what point did you start to use computers for music making and can you remember what your initial sequencer was?

Initially I used the UMI sequencer – the one that crashed every time you breathed. I then did a lot of stuff on my first solo album, Transportation, using Pro 24. I didn’t feel like a cheat because I’d been into technology for years but I did a whole piano track called Rakaia River (Mountains To Sea) using a Technics piano and Pro 24, no proper playing. When Miles Copeland came down and I told him, he looked a bit disturbed by the prospect. I had a blast creating that album though – using technology to the maximum.

Q. One of the things that many computer musicians complain about is how composing on a computer based sequencer can make them rather insular. Is that the case with you or do you prefer the ability to focus in isolation?

It was difficult back in the UMI days when I did a track called India, because that was a band and they’d get impatient watching things crash while I was trying to edit parts on it. Later with Notator things became a bit more collaborative because it was great for creating patterns, as opposed to Pro 24’s more linear approach.

The isolation works for me when I’m doing a solo record. But if you’re working closely writing a song with someone It largely comes down to who you’re working with. If it’s the kind of person who can’t do it unless they’re shutting everyone out, that can get irritating.

Q. You’ve kindly contributed patches to impOSCar2, Oddity2, VSM and RE-STRINGS. This prompted one impOSCar2 user to write to us saying that it was evident from your sounds that you knew the original OSCar inside out.

That’s nice to hear. I think it comes from the days when keyboards were expensive and you needed to know them inside out in order to get your money’s worth. Creating sounds with OSCar and the ARP Odyssey became second nature because I spent a lot time with them, both live and in the studio. String machines are easier to use and it comes down to character. As you know, I was never a fan of the Solina but the Elka Rhapsody and Yamaha SS-30 just had these qualities that connected with me. I’m just pleased that VSM & RE-STRINGS have both of these instruments.

Q. Does Oddity2 make an appearance on Doppel and if so can you give a name of a track where it’s easily spotted?

Yes. When we started working on the prototype back in 2014 I found a sound that actually started my whole album off. I loved it because it was a rubbery, repeating sound that reminded me of Steve Reich in 2050. It was just mad and I laid it down before playing some viola over it. It was very inspiring and that eventually became the track Gleam.

On Tremolo Shudder it was used for the bass part. That’s a tough sound with some amazing character.

In Full Cry, was all Oddity2 except the flappy rhythmic sound, which is Omnisphere. I used the sounds that I downloaded from your site earlier this year. Programmed by PKH. I loved them!

At the end of Viola Reach there’s a lovely rough, distorted sound from Oddity2 too.

Q. And VSM?

That’s noticeable on the track Tremelo Shudder. It’s more of a rock track really and it’s there because it’s heartfelt, emotional but threatening.

That’s the Elka sound but with some phasing on it. But that’s what got me going. In some ways I am a rock musician and if I’m there at the back of my studio, listening to something and it’s giving me the shivers, I’m happy. And that’s what VSM was doing.

It’s also there on a reworking of an old song I did on ‘Unearthed’ called Running Through the Years. I changed the name to Silver Tongued and did a much slower version of this melody because I just love the melody. It’s very classical but I wanted to do something else with it…so that’s the SS-30 but pure.VSM crops up time and again in the mix in various places but those are the most noticeable.

Q. Do you think you’ll tour your solo work?

Did I ever want to be a Jean Michel-Jarre? No, it’s impossible. It’s not just getting through the eye of the needle, it’s getting through the eye within an eye of a needle!

No. I’m more of a writer and while I like to play live, I get more excited by the writing process. Also, I have to battle something I think I’d need to be young to do. Did I ever want to be a Jean Michel-Jarre? No, it’s impossible. It’s not just getting through the eye of the needle, it’s getting through the eye within an eye of a needle! That said, there’s something about me that says I’d like to prove to myself that I could do it and I have had offers. I have to be realistic about it though and stop getting romantic about the idea it might happen one day.

Q. On the Return To Eden and subsequent Ultravox tours you used VSM, impOSCar and Oddity, live. Also Chris and Warren used Minimonsta for tracks like Sleepwalk and Mr X. Hearing our instruments through a big PA was a bit of a special moment for us.

That’s really good to hear. It did sound great from where I was and a lot of people commented that it sounded great from an audience standpoint, but when you’re on stage you have a different perspective and you don’t hear what the audience of a full concert hall hears. It’s reassuring that it sounded as good out front as it did to us on stage.

Q. We read recently that as far as your concerned Ultravox is definitely over. True or false?

Ultravox has been a huge part of my life for over forty years and I just want to draw a line under it. I don’t think that’s unreasonable, especially as ‘Doppel’ is my tenth solo album.

Q. What’s next on the agenda?

The ‘Doppel’ album is out and doing pretty well and I’ve already started some tracks for another album. I’ve got five ideas going which I actually started before I finished ‘Doppel’. That’s pretty unusual for me and I’m really looking forward to getting on with it when the nights start drawing in.

More info

Photos and images kindly provided by: Olaf Bärenfänger, Matthew Vosburgh, Freya Spiers & Billy Currie